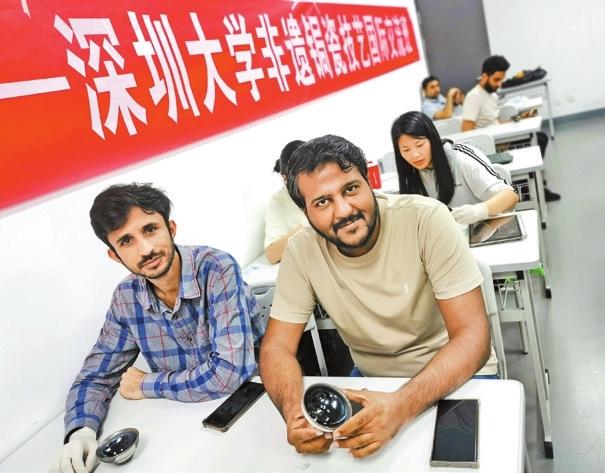

Students work on a kintsugi item at Shenzhen University on Sunday. Photos by Li Dan

A student presents her kintsugi piece.

Students present their kintsugi works.

Fang Ruihua (C) instructs a student during the course.

A student works on his kintsugi piece.

MORE than 60 students have enrolled in an 18-session kintsugi art course at Shenzhen University (SZU), the first time that an intangible cultural heritage is systematically taught to college students, who will earn one credit upon completing the course and creating one piece of kintsugi work.

The course, taught by Fang Ruihua, a fourth-generation inheritor of juci and kintsugi based in Bao’an District, is an innovative effort to enrich the school’s curriculum and disseminate Chinese cultural traditions.

“In the past, people would repair stuff when they were worn or broken, but nowadays, most simply throw them away and get replacements,” Fang told a fully-packed classroom at SZU’s Canghai campus Sunday afternoon. “For me, the act of repairing items to extend their lifespan goes beyond just practicing sustainability; it teaches us about accepting life’s imperfections, appreciating each other’s uniqueness, and understanding the value of endurance.”

Juci and kintsugi are both ancient Chinese ceramic restoration techniques employed to mend broken porcelain, pottery, and lacquer wares. While juci uses small metal staples to hold broken pieces together, kintsugi utilizes a special tree sap lacquer dusted with powdered gold, silver, or platinum as an adhesive to repair damaged items. Translating to “golden joinery” in Japanese, kintsugi is referred to in Chinese as “金缮” (pinyin: jīnshàn), meaning “repairing with gold.”

The exact origin of kintsugi remains uncertain. A popular story alleges that some Japanese craftsmen developed the technique after shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa in the late 15th century had his favorite Chinese tea bowl — which had been carelessly broken — repaired by juci in China and returned but disliked the visible metal staples. However, Fang suggests that like the tea ceremony and flower arranging, kintsugi has existed for centuries in China, but the Japanese refined these traditions as they became obsolete in their native land.

This centuries-old practice is often used to mend cherished objects by enhancing the cracks, which serve as a visual testament to the object’s history. Once completed, beautiful seams of gold or silver glint in the conspicuous cracks of ceramic wares, giving a one-of-a-kind appearance to each repaired piece.

Each attendee, many of whom were foreign students, received a small porcelain vase or bowl, which they then shattered into large pieces using a hammer. They meticulously applied adhesive to the edges of each piece before reassembling the item into its original shape.

The adhesive — a blend of natural lacquer extracted from the sap of the lacquer tree and flour glue — is glossy, robust, and waterproof. In cases where small sections of the original ceramic are missing, a paste comprising the adhesive and clay powder is used to fill the gaps.

“Working with the adhesive can be challenging due to specific requirements for it to harden, such as high humidity, and the lacquer itself can potentially cause skin irritation,” Fang explained.

The students were instructed to take their items back to their dormitories, leaving them to dry in the bathroom while taking extra care to prevent contact with water.

Teodora Lalovic, a student from Serbia studying Chinese at SZU, said the course was an enlightening experience. “Although I studied graphic design in my home country, I have never attempted this form of art before,” she said, adding that learning about Chinese culture and working with utensils will enhance her comprehension of 3-D models and inspire her future artistic pursuits.

Sophomore student Liu Miaosi said she enjoyed the course. “Engaging in manual work provides a therapeutic experience, helping me focus on the present and alleviate all worries,” she said. “It feels as though I have time-traveled to my childhood, playing with my favorite toy.”

Zhang Wenwen, a faculty member at SZU’s Media and Communication School, advocated for the integration of this course into the school’s curriculum. Leading a team of more than a dozen students dedicated to promoting cultural heritage, he expressed regret that certain traditions are better developed in other countries, with craftsmen from those regions revitalizing art forms like kintsugi.

“Hopefully, this course will pique the interest of more young individuals in our cultural heritage,” Zhang said.

(ShenzhenDaily)